The Status of Orcas in Canadian Waters (2021).

Orcinus orca, or commonly known as the killer whale or simply orcas, has been a constant inhabitant in Canadian waters for thousands of years. Their presence here has shaped the way the First Nations and Inuit Canadians have lived for generations. And up until the modern point killer whales, although not a dominant figure when compared to animals such as beavers or moose, have become accepted as a staple of depicting Canadian culture with an icon (see the Vancouver Canucks and modern Okanagan art). Since orca ranges are so vast across Canadian waters, specie differentiation can tend to occur. Two major orca families can be identified from this process based on geographic location – Atlantic (East + Arctic) and Pacific (West). The Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) recognizes both the western North Atlantic and eastern Canadian Arctic killer whale populations as a singular population [1]. It should also be mentioned that although somewhat reluctant, COSEWIC also identifies the lesser known western Canadian Arctic orca in this group as well. Meanwhile in western Canadian Pacific waters, three different distinct groups of killer whale populations are regularly identified by scholars and zoologists based on behavioural, genetic and geographic confines. The northern resident orca, southern resident orca and the transient killer whale. As such, COSEWIC currently lists the northern resident killer whale as threatened since 2001 [2]. While the southern resident killer whale was and still is recognized as endangered by the Canadian Species at Risk Act since 2001 and since 2005 by the American Endangered Species Act [3]. However, very little is known about the mammal-hunting transient orcas as they were only recently identified as a separate group. Therefore, no official recognition stands with reference to its status in the wild [4].

PAGE 1

With respect to the Atlantic Canadian killer whale populations, COSEWIC has them listed as of special concern [5]. Total numbers of identified whales exist due to intensive studies done in each region by researchers however, they are not fully definitive. As recent as 2020, 53 individual orcas have been independently identified in the eastern Canadian Arctic ecosystem specifically. These whales are also believed to visit and pass through Canadian Maritime waters as well, mainly while attempting to reach the Canadian Arctic [6]. In the Pacific, 212 northern resident killer whales and 89 southern resident killer whales have been identified to frequent British Columbian waters since 1998 [7]. No comprehensive evidence stands currently for accurate numbers of residing whales in Maritime waters. Globally, killer whales can be found in all oceans. Their adaptability as a top predator in virtually any ecosystem allows them to be spotted across the globe [8]. Therefore, their presence in international waters have been recognized. So much so, that their presence alone has become an entire industry in its own right. In a 1993 annual meeting by the International Whaling Commission, the board officially recognized “whale watching” as a viable and ever-expanding tourist industry to be supported; which can provide local economics another stream of revenue alongside also citing educational, scientific research and recreational based opportunities [9]. This new mode of ecotourism is not limited to killer whales alone and it is from this basis that killer whales are perceived globally as an admirable creature of the sea. A 1986 survey done in California found that 86% of respondents admitted that viewing a whale in the wild could be considered as one of their greatest outdoor experiences [10]. This sentiment of appreciation of killer whales is strong, yet the experience of animal-human interactions by orcas say otherwise.

PAGE 2

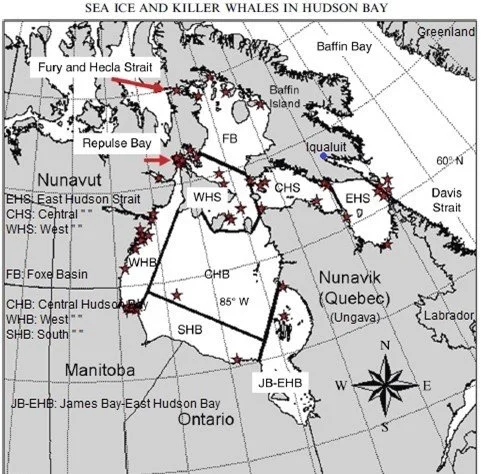

Despite public appreciation of killer whales, current threats on orcas pushing the species towards risk are to a great extent driven by anthropogenic factors. With Pacific northern resident and southern resident orcas being listed as both threatened and endangered respectively plus the free-range Atlantic-Arctic killer whales being categorized as of special concern, it would be safe to assume that, like all threatened species globally, human-induced factors can be at play. What first needs to be corroborated is that since the Canadian killer whale population is split into two major geographical regions (Pacific and Atlantic-Arctic), each group can experience both the same overall and different regional specific threats. However, it should be noted that both populations are currently facing significantly different dangers rather than similar ones. To begin with, Canadian Atlantic-Arctic killer whales are experiencing abrupt and unexpected changes to their range along with the lesser established possibility of elimination due to ice entrapments. Both of these which can be directly attributed to climate change [11]. It is unique in that the former interference cannot necessarily be interpreted as a direct threat. The abrupt and unexpected changes to the Canadian Atlantic-Arctic orca range are ones of growth and expansion because of the annually receding ice in the Arctic sea – something of which is a direct consequence of climate change. Areas of importance such as the Hudson Strait, Hudson Bay and Foxe Basin, which experience extreme deep freeze during the winter months, have been substantially frozen for now lesser periods of time [12]. Semi-fluid sea ice floating in the Hudson Strait have traditionally acted as natural barriers, stopping killer whales from migrating either west into Hudson Bay or north to the Canadian Arctic Archipelago [13]. As noted, the premature melting of sea ice has allowed for killer whales to not only enter the Canadian Arctic earlier but remain for prolonged periods of time. The continued presence of killer whales in the Arctic can be verified by Inuit observation for which they also believe is unnormal based on their traditional knowledge [14].

PAGE 3

What is important to note from this is that their occurrence in the Arctic can only be noticeable when sea ice is not present. Meaning that when sea ice is present, killer whales are not likely to be spotted [15]. Henceforth, it should be stressed that killer whale presence in the Arctic is only persistent due to longer durations of no sea ice. Not that when only minimal sea ice is present. The extension of the orca range may not seem concerning at a first glance since they themselves are not being affected detrimentally. However, the coinciding ecosystem of the Hudson Bay and Canadian Arctic Archipelago can be affected to a drastic degree with the extended presence of killer whales. It has been noted that the primary prey of killer whales in the Arctic remains largely unknown. Although, orcas have different options on their menu while here. A study done by a join Canadian-British-Greenlandic research team in 2013 found that migrating killer whales could potentially be thriving by preying on an established local population of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) residing in Eastern Canada-West Greenland. Their method of data collection was done through observational means, by distinguishing “rake marks” via photographs from 1986 and 2007-2012; detected on recorded bowhead whales. Observing rake marks are an efficient and well-established technique which is often used to determine if aquatic mammalian-like prey have been attacked by ocean predators. The most common process internationally observed is the rake marks done by giant squid attempting to prey on sperm whales in the deep sea. Sea mammals such as manatees or in this instance bowhead whales, are capable of retaining rake marks done on them by predators due to their skin and blubber composition – which can take many years or even decades to heal even if the wounds obtained are superficial. The paper identifies that from a total of 598 bowhead whales observed, 10.2% bore rake marks from killer whales [16].

PAGE 4

Other findings include determining consistencies between a temporal increase in bowhead whale rake marks and increased orca presence and that bowhead whale calves observed had less rake marks meaning that calves predated on are likely not to survive the event [17]. What is noteworthy is the observation of killer whales via rake marks being evident in as far north as Isabella Bay (P.O.I. #1) since 1986. Meanwhile, using the Foxe Basin as a reference point, rake mark appearances at Naujaat and Igloolik [#4] have without a doubt increased yet numbers from Isabella Bay and Cumberland Sound (#2) remain steady. This means that the Hudson Strait has as of recent been regularly opening up giving easier access to orcas into Hudson Bay and Foxe Basin [18]. The next threat is not as profound as any other threats distinct to killer whales however, is certainly of substantial merit and is worth discussing. Ice entrapments are quite rare but can be experienced by virtually all aquatic species residing in the Arctic.

A 2017 review done by a Canadian conservation team intensively studied 17 recorded incidents of killer whale ice entrapments from the mid-1800s to as recent as 2013. Of these 17 incidents, 6 occurred in Canadian Arctic waters – ranging from Newfoundland to Nunavik (Ungava/Quebec) and Nunavut. Reports of orca mortality, especially historic, remain difficult to interpret. Based on data ascertainable in the review, at maximum 13 known killer whales have died in Canadian waters directly due to ice entrapment since 1955.

PAGE 5

Points of Interest are as follows: 1 Isabella Bay, 2 Cumberland Sound, 3 Naujaat, 4 Igloolik & 5 Disko Bay.

Red dots indicate settlements.

Whereas 21 orcas have died from ice-related activities since the early-1900s [19]. Therefore, although not threatening to the point of endangerment or extinction, ice entrapment for the western North Atlantic and eastern Canadian Arctic killer whale population is a rare possibility that is worth acknowledging. It is due to these particular constraints that COSEWIC has Atlantic-Arctic orcas listed as of special concern rather than giving an official designation of threatened or endangered. Since no major threat exists impeding their well-being. Yet their presence alone is worth monitoring. However, the prospect for fellow orcas on the Canadian Pacific remains drastically different. Both the northern resident and southern resident killer whales are facing extreme threats causing for them to be classified as threatened and endangered respectively – all of which are anthropogenic. Climate change effects are not as defined for Pacific orcas. Instead, factors such as pollutant contamination, human presence and decrease in quality and quantity of resources are putting Pacific orcas at risk. A 1998 survey recorded that northern and southern resident orca numbers were at 212 and 89 respectively living in British Columbian waters [20]. Examination of southern residents specifically began in 1974 which counted 71 killer whales.

By 1996 there were 97. But an unpredictable and drastic decline of 20% in just five years after that count led to there only being 78 southern residents [21]. Persistent organic pollutant concentrations in Pacific killer whales are among the highest in the world’s cetaceans. POPs such as PCBs, DDTs, HCHs and other organochlorine and polybrominated compounds have been found to exist not only in coastal B.C. waters but subsist in Pacific killer whales substantially. Blubber samples from all three species, including the transient orca, have determined that the collective orcas are among the most contaminated in the world [22].

PAGE 6

A snippet of a map displaying orca ice-related incidents.

The existence of POP concentrations in Pacific waters can be attributed to agricultural and industrial runoff [23]. It is important to note that these POPs are found more in southern coastal waters which also explains why southern residents are more contaminated than northern residents [24]. POP contamination in orcas can lead to a number of detrimental immune, neurological and reproductive effects. It was found that contaminated adults, mainly mothers, are in a direct path to also contaminate weaning juveniles. Studies document the first born of every orca mother having the highest levels from birth. During lactation, the mother’s levels tend to decline as calves are weaning. Afterwards though, orca mothers’ levels of POPs tend to rise again [25]. Thus, POPs are attributed to developmental problems which can lead to premature death of Pacific orcas. This combined with the presence of human interference in their marine habitat has created a difficult environment for Pacific orcas to thrive in. Expanded boat presence and more importantly boat noise, as a result of ecotourism have significantly altered the way resident killer whales behave and navigate in B.C. coastal waters. Marine reserve areas such as the Robson Bight Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve based in the Johnstone Strait in northern Vancouver Island have standing unofficial rules asking boats to remain at minimum 100m away from visiting whales. However, across the island this code of conduct is regularly broken and boats even frequent reserve waters while being authorized not to [26]. Findings include the orcas spending less time rubbing on smooth pebble beaches when in the presence of boats (17% to 3%) and displaying significantly more energetic costs when around boats and suffering from hearing loss from boat noise – ultimately effecting communication and navigation abilities [27]. Overall, boat traffic has been recognized as a conservation concern for eastern Canadian Pacific killer whales.

PAGE 7

Social implications for Atlantic-Arctic and Pacific killer whales in Canada vary from each region. In the east, killer whales have coexisted with Inuit for centuries. Their presence has been long acknowledged and the mutual respect still stands. Up until now, killer whale diet has not been officially confirmed or even observed in the Canadian Arctic. It is only believed by both Inuit hunters and researchers that they feast on marine mammals at maximum and that no prey specialization among Arctic orcas exists – this includes hunting fish which is definitively non-existent. Therefore, it is hard to determine whether or not killer whales are infringing on the ability for Inuit hunters to hunt for food and gather resources for their communities [28]. Also, whale watching and ecotourism in the Arctic is not as feasible and viable. Plus, POP contamination with respect to biomagnification is non-existent or has not been known of. Thus, orcas here do not suffer from human interference. Which still corroborates the designation by COSEWIC as of special concern over threatened or endangered. Meanwhile in the Pacific, social implications for killer whales are more profound.

PAGE 8

Conservation efforts have actively determined that for orcas to not only survive but thrive in B.C. waters, ecotourism and overall human interaction must be limited to a substantial degree (Noren & Hauser, 2016, pp. 168, Jelinski et. al, 2002, pp. 393 & Williams et. al, 2006, pp. 301 & 308-309). This ultimately implicates that an implemented decline, whether governmental or social, must be put in place for the whale watching industry. Effectively justifying the need for a diminishing of local economies based on whale watching. Researchers have also continually called on policy-makers to restrict the amount of POPs entering the marine ecosystem, especially in southern Vancouver Island. The decline or potential loss of killer whales in the Pacific would also be believed to have a sociocultural effect on western First Nations such as the Okanagan – where the orcas have a significant importance. Nonetheless robust measures must be taken place, predominately in western Canada, in order to secure the well-being of Canadian orcas and this includes restricting anthropogenic activities involving interaction.

In conclusion, conservation efforts of killer whale populations in Canada is somewhat difficult to assess. On the one hand, Atlantic-Arctic orcas are doing substantially well and given that their established presence here has only been firm from around the previous 50 years, it is hard to determine whether or not such efforts are necessary. Yet on the other side of the nation, the well-being of Pacific killer whales is without a doubt being strained. Conservation efforts here are much more intact and are well coordinated by researchers, conservation boards and authorities.

PAGE 9

However, this still does not negate the fact that killer whale numbers here are dwindling. Conservationists here need to step up and urge policy-makers to create statues which actively limit human interaction and cap off chemical contamination. Laws are already in place which restrict whale watching, especially in conservation areas. These laws for conservation areas are in fact enforced yet still whale watching boats tend to make their way into these protected reserves and it may seem that such reserves are facing understaffing due to how often park enforcement officials report making their back into the waters to stop them. In essence, the region is superficially well off. Internally however, it could be considered as anything but. Killer whales are thriving in some regions and struggling in other regions. The different classification labels like threatened, endangered or special concern can make things tricky when looking to assess orca conservation prospects in Canada as a whole. Regardless, it seems as though the preservation fundamentals for killer whales to inhabit Canadian waters are in place. The question is if whether these basics will expand.

PAGE 10

References.

[1]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). “A review of Canadian Arctic killer whale (Orcinus orca) ecology”. Canadian Journal of Zoology, Vol. 98, Issue No. 4. pp. 246.

[2]: Williams, R., et. al. (2006). “Estimating relative energetic costs of human disturbance to killer whales (Orcinus orca)”. Biological Conservation, Vol. 133, Issue No. 3. pp. 303.

[3a]: Noren, D.P. & Hauser D.D.W. (2016). “Surface-based observations can be used to assess behavior and fine-scale habitat use by an endangered killer whale (Orcinus orca) population”. Aquatic Mammals, Vol. 42, Issue No. 2. pp. 168.

[3b]: Krahn, M.M., et. al. (2009). “Effects of age, sex and reproductive status on persistent organic pollutant concentrations in ‘Southern Resident’ killer whales”. Marine Pollution Bulletin, Vol. 58, Issue No. 10. pp. 1,522.

[4a]: Ferguson, S.H., et. al. (2016). “Review of killer whale (Orcinus orca) ice entrapments and ice-related mortality events in the Northern Hemisphere”. Polar Biology, Vol. 40, Issue No. 7. pp. 1,467.

[4b]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). “High PCB Concentrations in Free-Ranging Pacific Killer Whales, Orcinus orca: Effects of Age, Sex and Dietary Preference”. Marine Pollution Bulletin, Vol. 40, Issue No. 6. pp. 504.

[4c]: Williams, R., et. al. (2006). pp. 302.

[5]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 246.

[6]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 246.

[7]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). pp. 504.

[8]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 245.

[9a]: Jelinski, D.E., et. al. (2002). “Geostatistical analyses of interactions between killer whales (Orcinus orca) and recreational whale-watching boats”. Applied Geography, Vol. 22, Issue No. 4. pp. 394.

[9b]: Williams, R., et. al. (2006). pp. 302.

[10]: Jelinski, D.E., et. al. (2002). pp. 394.

[11a]: Ferguson, S.H., et. al. (2016). pp. 1,467-1,468.

[11b]: Higdon, J.W. & Ferguson, S.H. (2009). “Loss of Arctic sea ice causing punctuated change in sightings of killer whales (Orcinus orca) over the past century”. Ecological Applications, Vol. 19, Issue No. 5. pp. 1,365.

[11c]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 245.

[11d]: Reinhart, N.R., et. al. (2013). “Occurrence of killer whale Orcinus orca rake marks on Eastern Canada-West Greenland bowhead whales Balaena mysticetus”. Polar Biology, Vol. 36, Issue No. 8. pp. 1,134.

[12a]: Higdon, J.W. & Ferguson, S.H. (2009). pp. 1,366.

[12b]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 247.

[13]: Higdon, J.W. & Ferguson, S.H. (2009). pp. 1,366.

[14a]: Higdon, J.W. & Ferguson, S.H. (2009). pp. 1,365.

[14b]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 247.

[15]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 247.

[16]: Reinhart, N.R., et. al. (2013). pp. 1,133-1,134.

[17]: Reinhart, N.R., et. al. (2013). pp. 1,133-1,142.

[18]: Reinhart, N.R., et. al. (2013). pp. 1,138.

[19]: Ferguson, S.H., et. al. (2016). pp. 1,470.

[20]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). pp. 504.

[21]: Krahn, M.M., et. al. (2009). pp. 1,522.

[22a]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). pp. 504-506.

[22b]: Krahn, M.M., et. al. (2009). pp. 1,522.

[23]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). pp. 504.

[24]: Ross, P.S., et. al. (2000). pp. 507.

[25]: Krahn, M.M., et. al. (2009). pp. 1,525.

[26]: Jelinski, D.E., et. al. (2002). pp. 395-396.

[27a]: Jelinski, D.E., et. al. (2002). pp. 407.

[27b]: Williams, R., et. al. (2006). pp. 307.

[28a]: Ferguson, S.H., et. al. (2012). “Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews”. Aquatic Biosystems, Vol. 8, Article No. 3. pp. 1.

[28b]: Lefort, K.J., et. al. (2020). pp. 249-250.

[29a]: Noren, D.P. & Hauser D.D.W. (2016). pp. 168.

[29b]: Jelinski, D.E., et. al. (2002). pp. 393.

[29c]: Williams, R., et. al. (2006). pp. 301 & 308-309.

Works Cited.

Ferguson, S.H., Higdon, J.W. and Westdal, K.H. 2012. Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews. Aquatic Biosystems 8(3). https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/10.1186/2046-9063-8-3

Ferguson, S.H., Higdon, J.W. and Westdal, K.H. 2016. Review of killer whale (Orcinus orca) ice entrapments and ice-related mortality events in the Northern Hemisphere. Polar Biology 40(7): 1467-1473. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/10.1007/s00300-016-2019-6

Higdon, J.W. and Ferguson, S.H. 2009. Loss of Arctic sea ice causing punctuated change in sightings of killer whales (Orcinus orca) over the past century. Ecological Applications 19(5): 1365-1375. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/10.1890/07-1941.1

Jelinski, D.E., Krueger, C.C. and Duffus, D.A. 2002. Geostatistical analyses of interactions between killer whales (Orcinus orca) and recreational whale-watching boats. Applied Geography 22(4): 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-6228(02)00051-6

Krahn, M.M., Hanson, M.B., Schorr, G.S., Emmons, C.K., Burrows, D.G., Bolton, J.L., Baird, R.W. and Ylitalo, G.M. 2009. Effects of age, sex and reproductive status on persistent organic pollutant concentrations in “Southern Resident” killer whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin 58(10): 1522-1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.05.014

K.J. Lefort, C.J.D. Matthews, J.W. Higdon, S.D. Petersen, K.H. Westdal, C.J. Garroway, and S.H. Ferguson. 2020. A review of Canadian Arctic killer whale (Orcinus orca) ecology. Canadian Journal of Zoology 98(4): 245-253. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2019-0207

Noren, D.P. and Hauser D.D.W. 2016. Surface-based observations can be used to assess behavior and fine-scale habitat use by an endangered killer whale (Orcinus orca) population. Aquatic Mammals 42(2): 168-183. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/10.1578/AM.42.2.2016.168

Reinhart, N.R., Ferguson, S.H., Koski, W.R., Higdon, J.W., LeBlanc, B., Tervo, O. and Jepson, P.D. 2013. Occurrence of killer whale Orcinus orca rake marks on Eastern Canada-West Greenland bowhead whales Balaena mysticetus. Polar Biology 36(8): 1133-1146. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/10.1007/s00300-013-1335-3

Ross, P.S., Ellis, G.M., Ikonomou, M.G., Barrett-Lennard, L.G. and Addison, R.F. 2000. High PCB Concentrations in Free-Ranging Pacific Killer Whales, Orcinus orca: Effects of Age, Sex and Dietary Preference. Marine Pollution Bulletin 40(6): 504-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00233-7

Williams, R., Lusseau, D. and Hammond, P.S. 2006. Estimating relative energetic costs of human disturbance to killer whales (Orcinus orca). Biological Conservation 133(3): 301-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.06.010

Submitted: 31 March 2021.

Last Updated: 22 August 2022.